Ever have those moments on weekends or public holidays when you wake at your usual time, then realise there’s no pressing need to get up? If you go back for another couple of hours of shut-eye and use the handy excuse of “paying of your sleep debt”, you’re not alone. But can we really catch up on lost sleep?

Before we get to the answer, let’s look at the two main determiners of sleep and wakefulness: circadian rhythms and the homeostatic sleep drive.

Your circadian rhythm is often described as the body’s “natural pacemaker”. It controls a range of bodily cycles including the 24-hour cycle that regulates your degree of alertness at various times of day. The circadian rhythm effect on sleep continues on a 24-hour schedule, regardless of how much or little sleep we get.

Sleep debt relates to the second determiner: the homeostatic sleep drive or sleep pressure. This drive operates on a simple deprivation and satisfaction model – the longer you go without sleep, the sleepier you get as the sleep pressure or debt builds up.

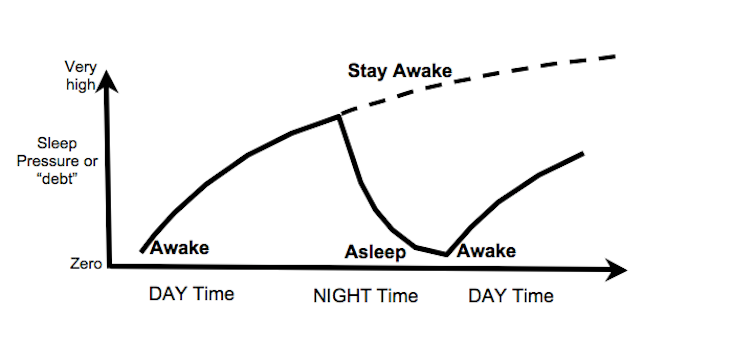

Sleeping then reduces sleep pressure or “pays off” the debt. This process can be illustrated simply in the diagram below.

When we wake up after a good night’s sleep and stay awake across the day, sleep pressure increases – rapidly at first then more slowly. Then after falling asleep, sleep pressure decreases, as the solid non-linear curve shows.

The diagram also demonstrates that not all sleep is equal in its ability to pay off accumulated sleep debt. The first few hours of sleep do this more quickly and efficiently that the last hours.

Feeling sleepy?

About a quarter of the Australian population reports rarely getting an adequate amount of sleep. Many more who feel all right would also probably get more sleep and feel better if they allowed themselves more opportunity to sleep.

Consistently getting too little sleep is a particular issue for new parents, who may be woken up every couple of hours to tend a hungry infant.

Shorter sleeps result in a higher starting point of sleep pressure. So for the chronically sleep restricted, the curve in the diagram above would start from a higher sleepiness value and increase in the same way across the day, but at a higher level.

This sleepiness gradually increases across days and there is strong experimental evidence that may result in higher rates of functional impairment.

Back to the weekend sleep in – this allows us to catch up on that lost sleep, doesn’t it?

It seems to; however, the experimental evidence for this is pretty sparse and not yet clear. What is clear from some studies is that sleeping in very late can delay the circadian rhythms and make it difficult to get satisfactory sleep the following week. So extending sleep on the weekends might not be that helpful after all. It’s better to get consistently adequate sleep across the week than trying to catch up on lost sleep at the weekend.

But what happens if you completely deprive yourself of sleep and stay awake instead of sleeping at night?

You guessed it – your sleep debt continues to increase. This is illustrated in the diagram by the dashed line.

Many total sleep deprivation studies have shown that you can fully recover after one to two nights of longer-than-normal sleep. Following a single night without any sleep, the recovery sleep the following night needs to be only two to three hours longer than normal to return most functions and mood to normal. After four or five nights of total sleep loss, a couple of longer sleeps are usually all that’s needed (12 hours, then ten hours, for example).

Following the documented, record sleep loss of 11 days by [Randy Gardner](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Randy_Gardner_(record_holder), an extra seven hours on the first recovery night sleep and extra three hours sleep on the second night seemed to return Randy to normal alertness and functioning, without any long-term negative consequences.

So a “debt” of 88 hours of sleep loss seemed to be repaid by an additional ten hours over Randy’s normal sleep need of eight hours.

So the evidence suggests that lost sleep can be recovered but our sleep debt doesn’t need to be repaid hour for hour.

Originally published on The Conversation