One of the most admirable and arguably underrated qualities of leadership is the capacity for reflection. Confucius called it the most noble way to learn wisdom.

But when we talk about what makes someone a successful leader, we typically describe attributes like the ability to innovate, make strategic decisions or manage uncertainty. We rarely mention reflection among the core traits of a great leader.

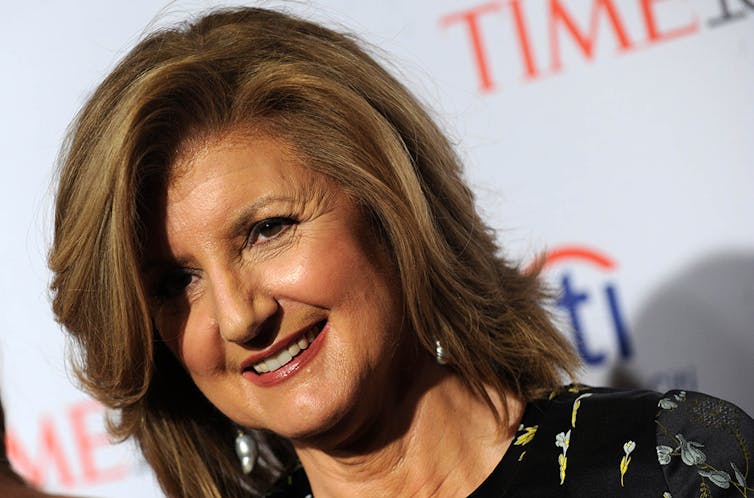

Yet their capacity to reflect on decisions, behaviors and learning certainly helped guide them toward success. Media mogul Arianna Huffington, for example, recommends reflection as a way to connect with one’s own wisdom and creativity. Billionaire investor Ray Dalio credits reflecting on painful experiences with helping him build Bridgewater, the world’s largest hedge fund.

Reflection is different than critical thinking, which is more focused on problem solving and an end goal. Reflective thinking helps us understand our underlying beliefs and assumptions and how they influence our decisions, guide us in problem-solving and drive behavior.

In my consulting work, I help organizations select top talent and rising stars who can achieve superior levels of performance. Companies tell me they want leaders who can make the “right” decisions quickly and decisively, often while balancing competing interests.

Given the fast-paced nature of the world we inhabit, it may seem counterintuitive for them and others to include the ability to reflect as among the most important traits that will determine a leader’s success. Yet there is growing evidence showing precisely that.

Power of reflection

Physicians understand this intuitively because they must make lightning-quick life and death decisions, requiring ways to help them navigate uncertain situations.

A 2015 paper on the role of reflection in bioethics education describes the ability to reflect as “crucial” to future physicians and helps them develop their “ethical and professional acumen and sensitivity,” according to researchers at Loyola University of Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, which integrates the topic into its formal curriculum.

As such, the school’s medical students participate in small group sessions and reflection-themed assignments that require them to examine their experiences in classes with questions like “What inspired you?” and “Do you feel you are becoming the physician you want to be?”

The majority of students who have participated in these programs said they found it helpful for their personal and professional growth.

Similarly, a year-long study by researchers at Tufts University School of Medicine and Boston College examined the role of reflection on physician-patient interactions. They found that physicians who reflected on the tone they used with patients – and how it affected the latter’s willingness to disclose information – led to improved communication and a greater emphasis on the patient’s actual experiences rather than their own perceptions.

Besides the potential for sharpened awareness and attentiveness in communication, reflection also boosts confidence in one’s ability to complete a task and also improves the understanding of the task, according to researchers at Harvard Business School. Perhaps surprisingly, they found that taking the time to reflect after finishing a job enhances performance more than additional experience doing it.

15 minutes a day

Although there is emerging evidence showing the benefits of reflection, why aren’t more leaders engaging in this activity?

There may be a host of reasons, the obvious answers being a lack of desire and time. According to behavioral scientists, most people prefer to engage in external activities rather than be alone with their thoughts.

A study of 1,114 chief executive officers in Brazil, France, Germany, India, the United Kingdom and the United States examined how they spend their workday. They found that on average CEOs spend about 70 percent of their time interacting with others either in-person or virtually. The rest is primarily spent on activities supporting these interactions such as travel and preparing for meetings.

This doesn’t leave a lot of time for focused reflection. Still, some leaders recognize the benefit of setting aside time to do just that.

For example, Harry Kraemer, the former CEO of Baxter International, schedules a nightly ritual of reflection during which he asks self-examining questions such as, “If I lived today over again, what would have I done differently?”

Kraemer doesn’t advocate a specific approach to self-reflection since he believes it to be a personal matter. But he strongly recommends that leaders make the time for it, even as little as 15 minutes a day. Interestingly, researchers have found that 15 minutes of self-reflection at the end of the day can in fact boost performance.

Spanx founder and billionaire Sara Blakely uses journaling as a means of reflection. In an interview, Blakely said she has filled about 20 notebooks with all the “terrible things” that have happened to her.

“Every terrible thing that happens to you always has a hidden gift and is leading you to something greater,” she said.

The idea that the best learning happens in moments of quiet reflection is a sentiment backed by research from the University of Texas at Austin. Researchers examined whether reflection enhances future learning. Participants were assigned memorization tasks and given time between them to think about anything. Participants, who used that in-between time to reflect on what they learned, became better able to connect new information to related ideas they already knew.

How to make it your own

So how can we all take advantage of the power of reflection?

The key, according to organizational psychologist Tasha Eurich, is to ask “what” rather than “why.” For example, instead of asking, “Why did this happen?” ask, “What could I have done differently to stop it from happening again?”

Asking “what” questions help us to escape the loop of rumination, maintain objectivity and stay focused on the future. When individuals take a “distanced perspective,” seeing things as an observer, they report higher levels of confidence and are able to better respond to sources of stress.

There is no unique universal approach to reflective inquiry. Investigate a practice that resonates most with you and apply it daily, beginning with minor challenges or even relatively benign situations.

There is no need to expect to get it “right and now.” The ultimate aim is to place yourself simultaneously as an active participant and observer of your life and experiences.

Originally published at The Conversation