As a child, I marveled at how migrating birds would descend on power lines, each seemingly equidistant from each other, as if they each knew precisely where to land, never too close, each perfectly spaced. No different, perhaps, than humans waiting in line to purchase a theater ticket on Broadway — each person standing just close enough — seemingly instinctively. Perhaps it was images like these, which we have all experienced, that drove the great anthropologist Edward T. Hall to study how the many varieties of animals in nature use space for social harmony — something he called the study of proxemics.

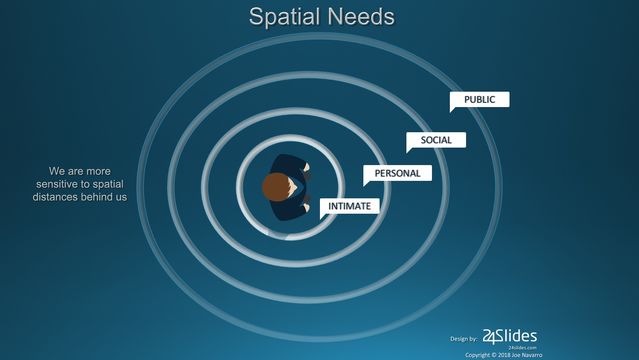

Proxemics has been very useful in understanding social interactions, whether that means children at play, colleagues sitting around a conference table, or just how many people you can pack into an elevator before there is a high degree of discomfort. Hall’s work has been widely cited by sociologists, psychologists, anthropologists, and even primatologists, because we all have spatial needs. Hall noted that there are four basic zones that we humans all share, and they vary in dimensions:

1. Public Zone: 12 to 25 feet, useful for public speaking and outdoor gatherings

2. Social Zone: 4 to 12 feet, a good social distance for interactions with acquaintances

3. Personal Zone: 1.5 to 4 feet, a comfortable distance for family and close friends

4. Intimate Zone: Skin to 18 inches, distances associated with whispering, touching, embracing, etc.

Note that these distances are approximations and can vary widely, as with the “public zone” above. What Hall also found was that when these spatial distances are violated, even by the well-intentioned, there are consequences — both psychological as well as physiological.

If a stranger stands too close to you, you may find yourself recoiling as your skin flushes, your heart races, your chest feels tight, and your lips compress, visibly showing your discomfort. These reactions are caused by limbic arousal — the subconscious activation of various systems within your brain to protect you and ensure survival. While all these things are taking place, there is “limbic hijacking” — your brain is so concerned with the psychological discomfort being caused that it takes precedence over anything being discussed. All we can think about is distancing ourselves, a phenomenon we have all encountered. (See the Dictionary of Body Language for more information about limbic hijacking.)

We are so sensitive about our space that when someone sits too close to us on an empty beach, we experience psychological discomfort, as we ponder why someone would unnecessarily sit so close. Or you step into an elevator and go to a corner; if the next person comes and stands right next to you, you become very uncomfortable. It is OK, when there are eight of you in the elevator, but not when there are just two of you. We evolved to react to spatial violations for the purposes of survival, and we have to be sensitive to spatial needs — our own and those of others.

Unfortunately, spatial needs vary by both culture and personal preferences, and it is not always clear what would satisfy each person. In many Latin American countries, people talk at distances many in the U.S. or in Norway, for instance, would find too close. While at the same time, many in Latin America would find that we in the U.S. stand too far away, giving the impression of coldness. While culture does influence how closely we interact, there are many other factors. Even within the United States, you will notice a difference between the spatial needs of a New Yorker versus those of a farmer from Des Moines, Iowa, or a Native American living along the Colorado river. These are all places I have been to, and how close people stand to interact is very different.

Fact is, there is no North American distance or South American, European, or Asian distance, only averages measured by those who study proxemics. While Hall’s work is useful, I have learned over four decades of observations that while cultural cues are important, in the end, as every diplomat soon learns, personal preferences trump social expectations.

Ask any group of people, and I do almost weekly in my seminars: How many of you have had someone stand too close to you while talking to you? Hands immediately go up. Seemingly everyone has had this experience. Why? Because we are taught to greet each other, but not how to do it — at least not as it relates to personal space that can vary from 1 and 1/2 to 4 feet.

If you are in the people business, and we are all in that business, or you are merely interested, read on.

First the space around us, as it turns out, is not perfectly symmetrical. We are more sensitive to violations of space from behind than from the front. Most people dislike if someone is too close to them at an ATM machine in the daytime and even more so at night. Our sensitivity to spatial needs goes way up when people are behind us. Again, this varies with individuals (see figure).

The time of day and the location will also factor in. In a secluded alleyway, we may feel uncomfortable with someone walking within 30 feet of us and again, at night, that distance may double or even triple.

Age and gender affect our spatial needs. A teenage girl may allow others to stand very close to her at a party (less than a foot or so), but by the time she is 35, she will require almost four times the distance. With age comes a greater need for space.

Emotions also affect our need for space. Couples who just had a fight may need 20 or more feet of space of separation (thus the often heard “You are sleeping on the couch”), while only a few hours earlier they were cuddled together. Alternatively, a tragedy in our lives may compel us to allow even strangers to hug us and whisper to us in our Intimate Zone, something we would never have permitted before.

People of higher social status, in almost every culture studied, prefer those of lower status to keep a greater distance. As I mentioned in the book, What Every BODY is Saying, when the conquistadores arrived in the so-called New World, they found that the king demanded greater space, just as in Queen Isabella’s court 5,600 miles away.

A person undergoing some sort of psychological distress may also require extra space. The clinically depressed have commented to me how they would prefer that others stand further away, even family members.

Grooming and smell affects our spatial needs. If someone appears to have not showered or changed their clothes in days or weeks, or they smell putrid, this causes us to want to stand further away.

The clinically paranoid personality, as well as those afflicted with schizophrenia, may become agitated if someone comes within distances that for most of us seem spacious, but for them are extremely troubling. I have seen some of these individuals complain when people would get within 30 feet of them. A problem for the mentally disordered in a crowded city.

We tend to stand further away from those who are agitated or fidgeting. Perhaps we innately recognize that we should give them more room. Likewise, we stand further away from those who talk too loudly or boisterously, and some will stand further back from those who gesture too much with their hands. Conversely, the hearing impaired will often stand closer to others, so that they can hear better.

There are other factors, as you can well imagine, such as our emotional state and whether or not the people around us are known to us or compete strangers. Regardless of this, in the end, what is important is to recognize that spatial needs are universal; however, the space each of us needs is not fixed and rigid, but rather fluid, governed by what we individually prefer.

It is up to all of us to assess for those preferences and spatial needs of others within the context of any given situation. This is where social intelligence comes in, as well as good manners. After all, we don’t want to be that person who is remembered for always standing too close.

What can we do to avoid standing too close? One way to accomplish this is to note before you approach someone the distance other people are standing from each other. This is not always available, nor perfect, but it is useful as a guide. Next, approach to greet the person just far enough to where you will have to lean slightly forward to reach out and shake hands. Then you will take a small step back and stand at a slight angle. If the person is comfortable at that distance, chances are they will not move. If they prefer you stand closer, this often happens in Latin America or in the Middle East, they will move closer to you. If they are uncomfortable, even when you took a step back, they themselves will step back even further.

Keep this in mind: Most people when asked would prefer others stand a little further back — it costs us little to accommodate others, and in the end, it will make everyone more comfortable.

Concluding Takeaways:

1. We evolved to react to spatial violations.

2. Spatial needs are first and foremost personal — everyone has their own preferences.

3. With age, our spatial needs change — they become greater.

4. Emotions often drive how close or how far away we want others near us.

5. Anger tends to make us want others at a greater distance.

6. How others smell may affect how far we want them to stand.

7. Emotional and psychological issues may compel some to become agitated if their space is violated.

8. It is up to us to assess for spatial needs in others based on context and their personal preferences.

9. It is safer and more comforting to stand a little further back from someone you just met.

10. When we respect the spatial needs of others, we help to contribute to psychological comfort.

Copyright © 2018, Joe Navarro, M.A.

References

Hall, Edward T.1971. Beyond Culture. New York: Anchor/Doubleday.

Hall, Edward T. 1983.The Dance of Life: The Other Dimension of Time. New York: Doubleday.

Hall, Edward T.1969. The Hidden Dimension. Garden City, NY: Anchor.

Hall, Edward T.1959. The Silent Language. New York: Doubleday.

Navarro, Joe.2018. The Dictionary of Body Language: A Field Guide to Human Behavior. New York : Harper Collins.

Navarro, Joe.2010. Louder than words: take your career from average to exceptional with the hidden power of nonverbal intelligence. New York : Harper Collins.

Navarro, Joe.2008. What Every Body Is Saying. New York: Harper Collins.

Navarro, Joe.2005. “Your stage presence: nonverbal communication.” In Successful Trial Strategies for Prosecutors. Candace M. Mosley ed., Columbia, South Carolina: National College of District Attorneys: 13-19.

Originally published at Psychology Today