In the early days of COVID-19, we faced many difficult decisions in everyday life: trying to weigh risk and decide whether to meet up or stay home, send kids to school or visit the gym. Now that my home state of California has its “shelter in place” order—and many other cities and states are in various stages of lockdown—a waiting period has taken shape.

In some ways, this is a relief—our minds get decision fatigue in the face of so many choices. Now we have our instructions, which are restrictive but useful to our brains. But many other types of uncertainty still remain, about things like our jobs, whether we will get sick even while taking precautions, or when we will see our loved ones and return to some normal routines.

We do not do well with uncertainty, and it drives much of the anxiety in the world, even when we’re not facing a pandemic. In fact, I define anxiety loosely as “an unrealized fear that thrives in uncertainty and other vague circumstances.” In the face of the unknown, we speculate, we avoid, we try to control. We “research” and confirm what we are afraid of.

This is not a good place for our thoughts. As a psychotherapist, I know that getting through this time will involve getting a grip on our minds. We need to focus on what is reassuring and positive, and what we can control. We can control our minds, at least to some extent. We can start small. Here are some things to work on.

Try: Structure your time

Reason: Routines are calming for everyone. Whether for children or adults, our minds need to know what to expect next. Anxiety thrives in vast amounts of unstructured time.

My sister-in-law Bonnie ran a daycare, and I am convinced that part of the reason she survived is because she gave each week a theme. We are all now running daycares of actual human gremlins or just the gremlins of our mind. Make a theme to your day, or a specific focus to your work. Bugs. Harry Potter. Ending emails as positively as possible. Walking or stretching during all phone calls. The focus doesn’t really matter, but it will help you make sense of the day. Remember, your mind wants to put order to things and when you don’t provide enough structure, it will spiral out on you.

Make a bucket list of things you will do during this time, and prioritize those that lead to a measurable result. Start with a morning routine. Keep it simple. Weed a corner of the yard. Cook a new recipe. Make a meal plan with all the groceries you just stocked up on. (I know I saw you at Trader Joe’s today!) Meal plans are great for uncertainty; even if you are just microwaving something, it is one more thing you can count on to go as planned.

Include essential tasks for your job and schoolwork when appropriate, but keep your expectations low. Even with extra time at home, we are cramming in work and usually more cooking and child care. At the very least, we have more interruptions and more temptations to procrastinate.

If you are working from home, don’t forget to make time to take a walk around the block, and plan to catch a sliver of the news and know when you will stop. Schedule news check-ins as if they are meals; no snacking.

Try: A news break

Reason: Our brains need to return to baseline functioning without constant stimulation from a fear-inducing topic.

Constantly taking in news headlines about infection, risk, and death stokes our fear engine, and we have to work hard to keep our worries in check due to our brain’s negativity bias: our tendency to pay more attention to the bad rather than the good. Consuming lots of news is not tolerable long-term for most people. Most of us could use a break for an afternoon, or even a full 24 hours to reset ourselves in the world and show up calmer.

Avoiding the news for a day makes our “wise mind” available when we do tune back into news. “Wise mind” is a term from dialectical behavioral therapy that refers to a way of looking at things with perspective and acceptance, or “peace in the truth.”

Instead of checking the news, notice what happens if you take a walk in nature. Nature has huge stress-relieving effects. The birds aren’t worried. The trees are growing. Your body is working. You can remind yourself that some basic things are still in place.

When you do need to tune back in, you want to be able to do this from a calm place. Wise mind gets chipped away by too much news and stimulation.

Try: Thought charts

Reason: Thought charts help you see a choice in what you focus on, and try to shift your perspective to a plan of action instead of worry.

It doesn’t do us any good to ruminate (“when your thoughts go in a circle,” as my son says). Ruminating thoughts feel like the devil on your shoulder, the worry cloud, or the buzz of anxiety.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most evidence-based way to address fear and ruminating thoughts, including issues like depression, anxiety, and insomnia. CBT is used for specific phobias, as well as widespread unease. With practice, it teaches you to reframe your thoughts in a way that generates less reactivity and more measured responses. CBT also happens to be the best treatment for those on the obsessive-compulsive spectrum, which recently has come to include many of us. (Who isn’t having recurring thoughts on coronavirus?)

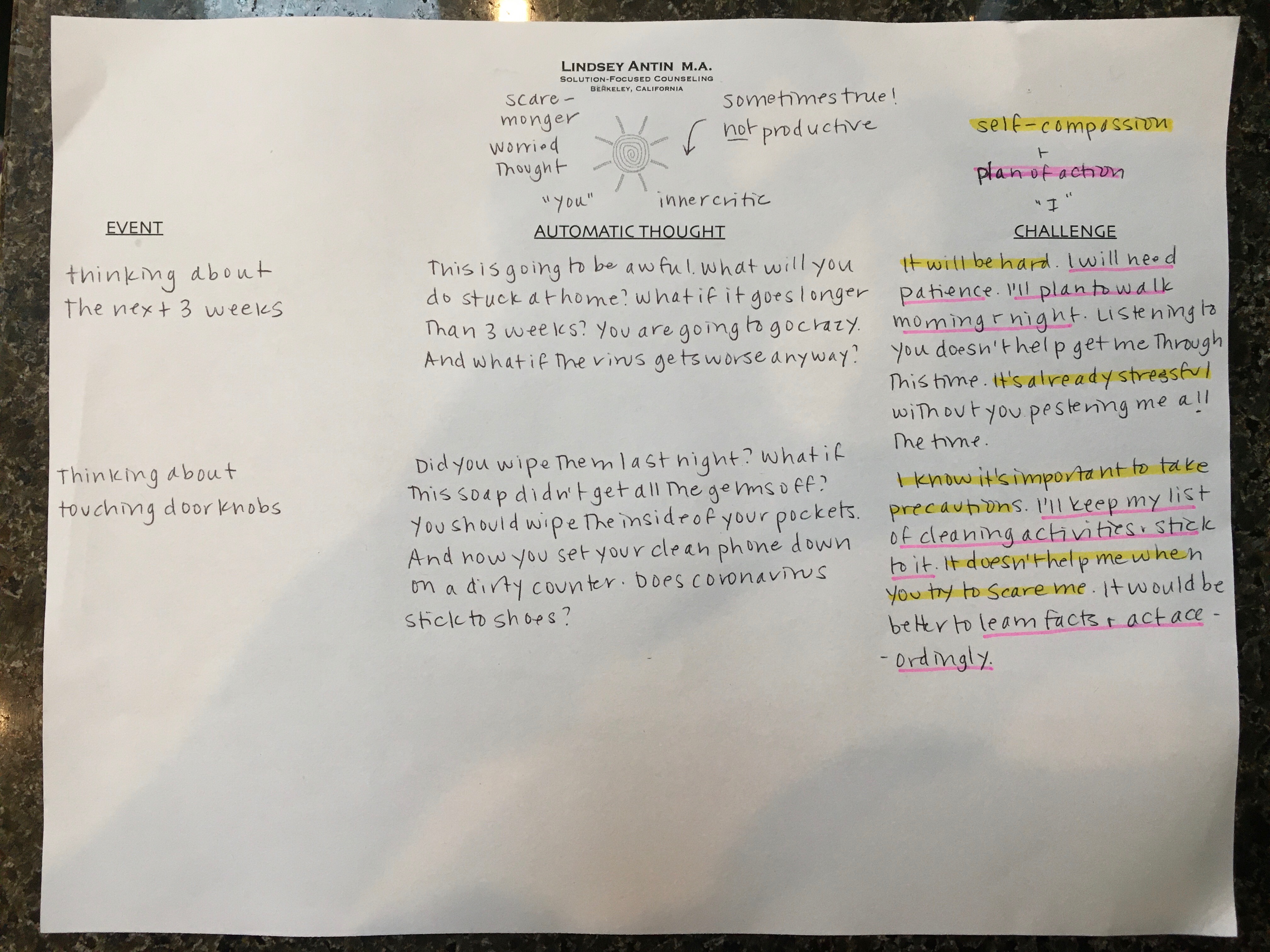

One helpful technique from CBT is to create a thought chart: This includes three steps: identifying the thought that creates concern, sometimes called an “event,” followed by the actual worried thoughts, and finally a challenge to them. The challenge to these worried thoughts should include self-compassionate phrases (“It’s normal to be worried right now”), as well as plan-of-action phrases (“Listening to the worried thoughts aren’t helping me so I will take a walk and play a non-news podcast”).

Thought charts help you look at the thoughts you have about yourself, your future, and the world around you—and see what messaging you’re giving yourself based on these thoughts. For example, at this time many of us are looking at the world around us and telling ourselves we ought to be afraid, and speculating on worst-case scenarios.

However, we can’t know the future, and with practice we can learn that this repetitive messaging is not productive for our lives. We can acknowledge the truth of our thoughts (if evidence supports it) and then add our own choice of response that includes two things: self-compassion and a plan of action.

We might respond to these worried thoughts by saying, “It’s true that coronavirus is out there, and that is scary [self-compassion]. What steps can I take so that I can still do what I need to do while following public health recommendations [plan of action]? When I let fear run my life, I don’t feel any better protected, so I’m not going to listen to this thought any more today.”

With practice, thought charts validate our anxious thoughts without letting us become trapped in them. We can see a clear choice and practice giving power to the self-compassionate and action-oriented thoughts.

Especially since we are all in this same situation together, we owe it to ourselves to figure out how to not let that terrified little part of us run our lives. The world needs us to bring our wise minds to action.

Written by BY LINDSEY ANTIN

Originally published at Greater Good Science